Genetically enhanced (GE) crops, pesticides, and fertilizers have fueled an explosion in food production over the last six decades. Following the pioneering work of Norman Borlaug during the Green Revolution, agricultural output began a dramatic climb from just over $1 trillion annually in 1961 to more than $4 trillion per year in 2019. This staggering increase has spared more than a billion people from starvation and improved living standards worldwide. A large body of research and real-world experience have confirmed time and again that restricting access to better seeds and crop chemicals traps the poorest people in a cycle of poverty.

This evidence is compelling to anyone who will consider it fairly, but there is a dedicated cohort of ideologues that refuse to let the facts frame their conclusions about modern farming practices. That description could apply to any number of publications or activist groups, but I have in mind Jacobin Magazine, “a leading voice of the American left, offering socialist perspectives on politics, economics, and culture.”

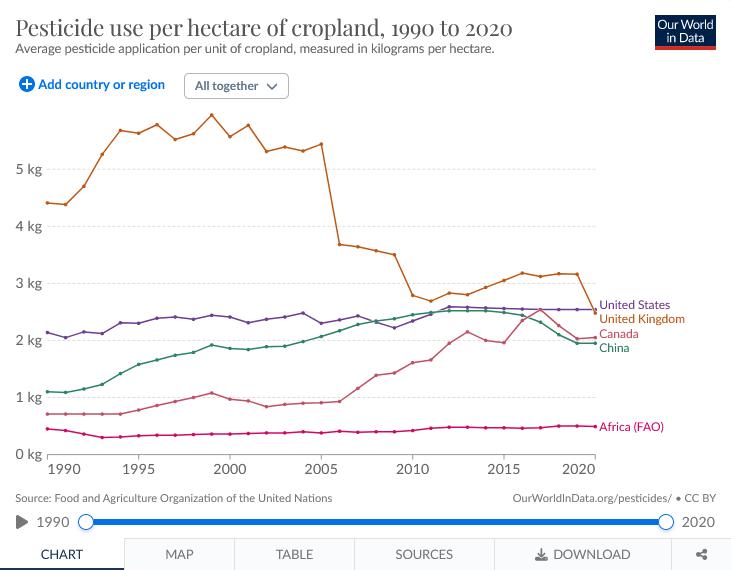

Credit: Our World In Data

In late September, Jacobin published a lengthy piece claiming that “Rich Philanthropists Don’t Have the Solutions to Africa’s Hunger Crisis.” Author Jan Urhahn, head of the “Food Sovereignty Program” at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, alleged that the nonprofit Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) had failed to halve hunger and poverty in several African countries by promoting the use of biotech crops, pesticides, and other inputs.

Not only is the story crippled by numerous factual errors, its author is a wealthy Westerner trying to force his agenda on Africans—totally undermining the article’s thesis.

Chains of stupidity

Urhahn's central claim is that AGRA, an African-led nonprofit funded in part by the Gates Foundation, puts smallholder farmers in “chains of dependency” by giving them access to agricultural inputs they won’t be able to afford long term, and that don't improve their crop yields:

"AGRA’s narrative is that by using more agricultural inputs, small-scale food producers will double their crop yields — which in turn will effectively double incomes, supposedly. According to AGRA’s evaluations, however, revenues from the sale of its main crop, maize, are very low."

AGRA has indeed acknowledged that it could do more to improve agricultural productivity in Africa. However, Jacobin wrongly implied that the alliance’s limited success in some countries is inherent to its “corporate-driven ‘Green Revolution’ approach.” That’s just false. Of the 54 African countries, only seven have regulations governing biotech crop cultivation, which is a significant barrier to distributing enhanced seed to African farmers.

One of the key reasons for this sclerotic regulatory outlook is political opposition “in most cases fueled by anti-GM activism,” according to a 2020 analysis. If Urhahn wants AGRA and related organizations to succeed, he should tell his employer to stop lobbying against GE crops and other technologies in Africa.

Related hurdles include import restrictions, high taxes on agricultural equipment, and inadequate systems for distributing subsidies to farmers in rural regions of many African countries. AGRA has to work with lawmakers and regulators to resolve each of these issues in individual nations before they can achieve additional progress. The Jacobin piece ignored these critical points.

Productivity kills poverty

Nevertheless, introducing enhanced crops to African farmers has yielded some major successes. As I wrote last year in response to the Non-GMO Project, more than 100 drought-tolerant maize varieties have been released in 13 African countries since 2006. Field trials showed that these crops, by withstanding harsh growing conditions, can increase yields by as much as 35 percent. Two million farmers in sub-Saharan Africa currently grow these maize varieties. The results thus far have been impressive:

"Farmers are reporting yields 20–30% above what they would have gotten with their traditional varieties, even under moderate drought conditions. If farmers continue to adopt the technology, the project has the potential to reap nearly USD 1 billion in benefits to farmers and consumers." [my emphasis]

These yield increases translate into greater profits and improved living standards for some of the poorest people in the world. According to one study conducted in Zimbabwe:

"DT [drought tolerant] maize seeds gives an extra income of US $240/ha [hectare] or more than nine months of food at no additional cost. This has huge implications in curbing food insecurity and simultaneously saving huge amounts of resources at the household and national levels ..."

These are precisely the results we’d expect to see if AGRA’s Green Revolution-inspired approach works. When wealthy businessmen—let’s call them “capitalists”—finance the development and distribution of yield-boosting seed, fertilizer, and pesticides, they enable farmers to be more productive. That productivity boost sets in motion a series of downstream effects that improve everyone’s well-being. To challenge this assessment means denying that lower production costs and food prices are beneficial. That, of course, is utterly absurd.

Pesticide poisoning mathmagic

The Jacobin story also featured the anti-pesticide messaging required of every article in this genre. Pesticides are poisonous, and we’re forcing them on unsuspecting African farmers, the argument goes:

"…According to a study in 2020, 385 million people worldwide suffer from acute pesticide poisoning every year … These pesticides are not good enough for Europe or the United States; these harmful substances however flood the African market thanks to organizations such as AGRA and others and pose a threat to African farmers."

That 385 million figure is a questionable estimate, at the very best. The researchers only had data for 7,446 fatalities and 733,921 non-fatal cases of alleged pesticide poisoning reported by individual studies. They had to extrapolate up to 385 million, and there are several reasons to suspect that they couldn’t do so accurately. Here’s my favorite:

“... [I]n most studies (57%) poisoning was self-reported to field researchers mainly based on a provided list of symptoms of pesticide intoxication.”

An extrapolation is only as strong as its weakest link, as my colleague Dr. Chuck Dinerstein has explained elsewhere. I can’t think of a weaker link than self-diagnosed pesticide poisoning. No clever statistical footwork will excuse a study based on such uncertain data.

Credit: Our World In Data

Whatever the actual number of poisoning cases, groups like AGRA have not flooded Africa with dangerous crop-protection chemicals. Poisonings are usually an issue because farmers misuse or overuse pesticides in a desperate attempt to protect their harvests. Sometimes, these products are illegal and adulterated, amplifying the risk they carry.

Reducing the use of these dangerous chemistries is a laudable goal, and the biotech crops Jacobin foolishly attacked could help make it a reality since insect-resistant crops need far fewer insecticide treatments. Properly educating farmers about pesticides and ensuring they have access to quality products is also important, which is why AGRA focuses on those very issues.

Other pesticides used in Africa are routinely employed in developed nations. Jacobin complained that AGRA projects in Ghana utilize the “controversial” herbicides glyphosate and oxyfluorfen, though it’s not clear why this is troublesome. There is no evidence that glyphosate causes cancer and plenty of evidence that it’s responsible for significant increases in farm income globally. Oxyfluorfen is also widely used, and the European Food Safety Authority identified “no apparent risk to consumers” when it reviewed the herbicide in 2020.

Stay out of Africa?

All these errors aside, the truly inexcusable aspect of the Jacobin story was Urhahn’s hypocrisy. He complained that “rich philanthropists” have forced their agribusiness model on Africa. Yet, he is employed by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, a Germany-based, government-funded nonprofit that lectures African countries about supporting "corporate-controlled seed systems."

Urhahn's advice to African governments on farm policy.

And although remembered as a communist revolutionary today by her acolytes, Luxemburg herself came from a wealthy family in Poland. Jacobin clearly doesn’t have a problem with the wealthy influencing policy in Africa, so long as they’re democratic socialists with a healthy appreciation for Karl Marx.

The matter is made worse because many farmers in the developing world have made clear that they want access to the same inputs their counterparts in the West utilize. From Kenya to India and Mexico, growers denied legal access to biotech crops, for example, acquire them illicitly because they see the value in the technology. Some scientists and farmers are so fed up with the “radical agenda” of groups like the Luxemburg Foundation they’ve given it a name: green neo-colonialism.

So, let’s modify the headline of Urhahn’s article to reflect reality: Rich socialists don’t have the solution to Africa’s hunger crisis—but they’ll force it on farmers anyway.