In 1898, under Roosevelt’s bully leadership, the Rough Riders invited Ivy league athletes, glee club singers, Texas rangers, and Native Americans to join the frontiersmen, in short, anyone skilled on a horse and eager to see combat.

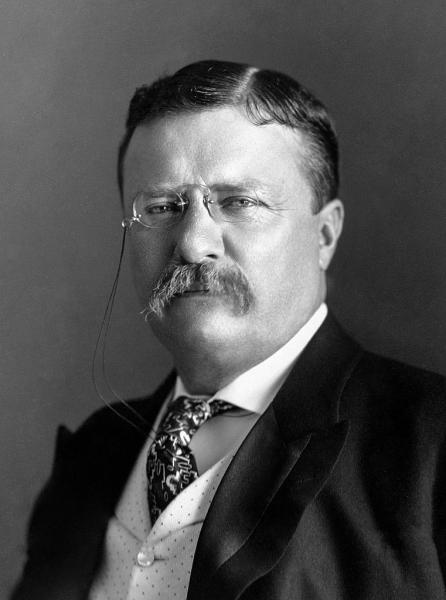

By 1901, when elected as the youngest President in the nation’s history (as a Republican progressive), he had already written a history of the war of 1812, been educated at Harvard, suffered asthma as a child, been felled by the psychological impact of losing his wife and mother on the same night, served as Governor of NY, and Secretary of the Navy, and succeeded in commandeering great respect for the naval prowess of the US.

By 1901, when elected as the youngest President in the nation’s history (as a Republican progressive), he had already written a history of the war of 1812, been educated at Harvard, suffered asthma as a child, been felled by the psychological impact of losing his wife and mother on the same night, served as Governor of NY, and Secretary of the Navy, and succeeded in commandeering great respect for the naval prowess of the US.

As president, he was known as the power behind the great trust-busters, cultivated Booker T Washington, and dealt with corruption in the Post Office and conflict in railroad rates. And yet, his greatest impact on us today are the Pure Food and Drug Act and Meat Inspection Act of 1906, the regulatory basis of the FDA. He served as the honorary American School Hygiene Association president and convened the First White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children in 1909.

While some credit Roosevelt’s childhood asthma as inspiring his interest and impact on health, sometimes times do make the man. 1906 was the watershed moment in exposing adulterated food practices – especially levied against the newly burgeoning immigrant population.

The unraveling began with the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which graphically depicted the extent of food adulteration, unsanitary and inhumane practices in the meat industry in Chicago. So extreme were the conditions portrayed that finding a publisher was difficult for fear of defamation. Initially published in a Socialist magazine, Appeal to Reason, in 1905, Doubleday, Page, and Company had the book investigated. After a series of inspectors were dispatched verifying the abysmal conditions, they agreed to publish it - the book hit the press and caused the uproar that resulted in both the Meat Inspection and Pure Food and Drug Acts.

The unraveling began with the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which graphically depicted the extent of food adulteration, unsanitary and inhumane practices in the meat industry in Chicago. So extreme were the conditions portrayed that finding a publisher was difficult for fear of defamation. Initially published in a Socialist magazine, Appeal to Reason, in 1905, Doubleday, Page, and Company had the book investigated. After a series of inspectors were dispatched verifying the abysmal conditions, they agreed to publish it - the book hit the press and caused the uproar that resulted in both the Meat Inspection and Pure Food and Drug Acts.

"I aimed for the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach."

- Upton Sinclair

President Theodore Roosevelt read and was deeply affected by Sinclair’s book, so much so that Sinclair embarked on a feverish correspondence with the president. (Similar reactions came from Winston Churchill). But, Roosevelt, too, was suspicious of the veracity of the allegations, especially given Sinclair’s socialist leanings and Roosevelt’s Republican affiliation.

To confirm the findings, Roosevelt sent the labor commissioner Charles Neill and social worker James Reynolds to make surprise visits to meat-packing houses in Chicago and write an independent investigation. Their report concluded that the meat packers of Chicago worked "under conditions that are entirely unnecessary and unpardonable and which are a constant menace not only to their own health, but to the health of those who use the food products prepared by them."

The Pure Food and Drug Act, of course, morphed and became the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act with authority over medical devices, cosmetics, and now health food products, but its beginnings arose with Roosevelt’s interest and investigation.