When I first wrote Antibiotics – The Perfect Storm (2009-10), I described the various factors that went contributed to the conundrum that still confronts us today.

1. Antimicrobial resistance, especially to our last line agents, was increasing.

2. The discovery of new antimicrobial drugs was incredibly difficult.

3. The regulatory environment at FDA was toxic to antibacterial development.

4. Clinical development of new antibacterial drugs was becoming more expensive and more time consuming.

5. The antimicrobial market was becoming more genericized. Resistant infections, although increasing, were still not common enough to provide for sufficient use of new antibiotics. The conditions were such that recouping any return on investment was becoming impossible.

6. This perfect storm was leading to an almost total exit of large pharmaceutical companies from the antimicrobial research space.

So, here we are almost 15 year what has changed? Unfortunately, most things are even worse today. The one encouraging note, from my view, is the Qpex-Shionogi deal that provides an example of how a large pharma can invest in antibiotic R&D and help to provide access to new antibiotics for LMIC countries as well.

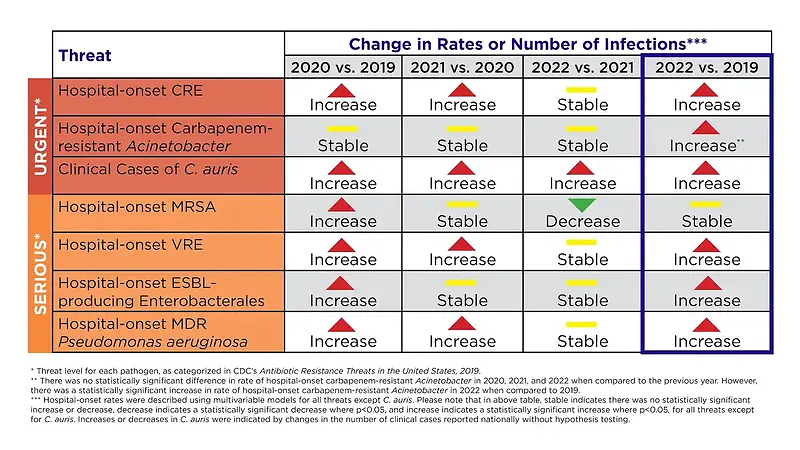

In 2024 US CDC reported that antimicrobial resistance had increased 20% overall between 2019 and 2022.

They (CDC) attributed this increase, that peaked in 2021, to, among other things, increased antibiotic use in hospitals during the Covid pandemic – especially early on when desperately ill patients were often treated with empiric antibiotics.

This probably occurred because physicians could not easily rule out a bacterial infection even in the presence of documented Covid. With time came more familiarity with the manifestations of covid and decreased use of antibiotics.

A recent publication from GARDP documented the ongoing difficulties discovering new antimicrobial drugs. They screened 48,015 compounds for activity against key Gram-negative pathogens. The compound library had previously been enriched for those likely to be active against Gram-negative bacteria. They were unable to progress any compounds into further discovery work. Their work mirrors previous work from GSK. I’m not sure antibacterial discovery is any more difficult than it was 30 years ago.

On the other hand, the regulatory environment, especially that in the US has improved considerably since 2009. Back then, the US FDA was, shall we say, lost. They didn’t understand how to deal with the non-inferiority trials that antibacterial developers depended on then and continue to utilize today. From 2006 to 2012, antibacterial development in the US had come to a virtual halt. When the FDA finally realized that their lack of clear policies and their dithering with infeasible trial designs had led to a lack of new projects to the point where the antibacterial group at FDA had little to do other than dither, under pressure from top management, they finally rebooted their approach. Since then trial design guidelines from FDA have at least become feasible and, in addition, fast development pathways using smaller patient populations have become available both in the US and EU.

In my view there remain at least two ongoing regulatory issues for antibacterial developers. The trials that would have to occur in very small populations for antibiotics specifically targeted towards single bacterial species or genera remain a significant challenge for regulators and developers. The approval of sulbactam-durlobactam for hospital acquired pneumonia caused by Acinetobacter is encouraging in this regard.

The other problem remains the often costly obligations of post-approval work that regulators require. This is a continuing difficulty for some sponsors (see below).

The antibiotic marketplace has continued to evolve since 2009 – and not in a good way. The population of patients requiring new antibiotics active against resistant infections remains small. An informal price cap in hospital pharmacies prevents the kind of high prices that would be required for any reasonable return on investment in these circumstances. Often, hospitals would rather take a chance on a less expensive antibiotic that might not work than use an expensive new drug that would be more likely to work.

Starting around the year 2000, the vast majority of large pharmaceutical companies that had been committed to antibacterial discovery and development began their exit from the field. The perfect storm supplies multiple reasons for their exit. Today, few large companies left have small ongoing efforts. What has evolved is that small biotech has taken over. They are responsible for over 90% of the antibacterial drugs in clinical development and most of the pre-clinical pipeline as well.

The loss of large pharma from antibiotic R&D has several implications – none of them good for antibiotics. The first is that these companies lose their internal expertise. So even if they were to become interested in in-licensing an antibiotic from a small company, they no longer have internal experts to help carry out appropriate due diligence. The loss of large pharma also robs small biotech and their investors of their favorite exit – purchase of the company by a large pharma. This is one of the main motivators for potential investors to shun antibiotic biotechs.

This evolution of antibiotic R&D from large to small pharma has advantages and disadvantages. The big positive is that there are still people out there working to bring new and needed antibiotics to the physicians and patients who need them. The major problem is that these companies are small, often inexperienced, lack breadth of scientific support and are often financially tenuous. For those companies who have only a single product in discovery or development stages, failure of the product means failure of the company. This provides a strong motivation to keep going in spite of strong data suggesting they should not do so. Another major problem is that the instability of this antibiotic discovery and development universe leads experienced scientists to leave the field either because their company has failed, sometimes that being their 2nd, 3rd or 4thcompany failure, or because they feel too insecure in the future of antibacterial research to continue.

And worse, these small companies often are unable to meet the demands of commercialization in a world where their products are kept in reserve, where regulatory post-approval obligations are ever weightier and where their market share grows at a tectonic pace. The vast majority of small companies that have brought antibacterial products through to FDA approval in the last decade have either gone bankrupt or been sold at pennies on the dollar shortly after approval. This, more than anything else today, threatens the future of antibiotic R&D.

If we want a future where we still have access to new and needed antibiotics, the answers to the perfect storm today are not much different than 20 years ago. In priority order . .

· We need to support the antibiotic market with large pull incentives (PASTEUR Act) – first and foremost. This will ultimately, hopefully, bring some large pharma back to antibiotics and therefore stimulate investment by providing an exit for small biotech investors. In turn this will stabilize the employment situation for antibiotic researchers and stem the ongoing loss of expertise from the field.

· Continuing support for antibiotic R&D is required.

· We need to continue to innovate on the regulatory side of the equation.

Time is running out. Our pipeline remains tenuous at best. Further biotech failures are likely. This will, in turn, lead to the loss of the paltry private investment occurring today and will contribute to the accelerated loss of expertise from the field. Our best solution is to pass the PASTEUR Act in the US.