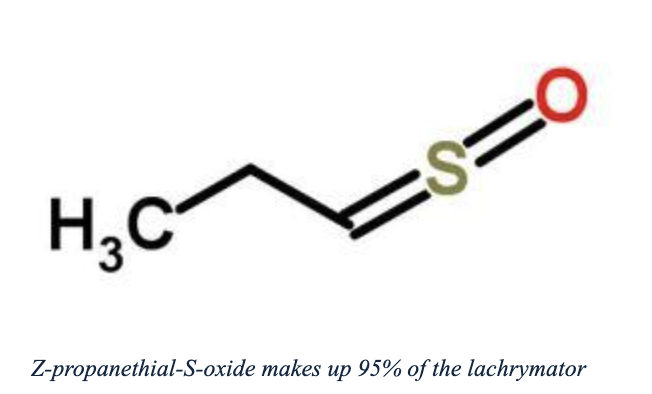

A lot has been written about why onions make you cry, but some of it is incorrect. Discovering the truth might be more entertaining than the fact itself. A 2012 chemistry textbook, a PBS site, and chemistry.about.com claim that the volatile lachrymator propanethial-S-oxide, produced by a cut onion's enzymes, reacts with water in the eyes to form sulfuric acid. However, sources like Scientific American and Onionlabs.com attribute the tearing effect directly to the molecule's action on eye receptors, with sulfuric acid not being involved.

Doubt arose about the sulfuric acid claim. If the lachrymator degrades so quickly in the eye's watery environment, wouldn’t it mostly break down in the onion itself? Assuming some lachrymator escapes due to its relatively high vapor pressure, I tested this by sealing onion pieces with wet litmus paper in a plastic bag. If sulfuric acid formed, the litmus should have turned red, but it didn’t, consistent with the lachrymator having no measurable acidity.

Some argue that the acid amount was too small to affect the litmus. Research mentions that each milliliter of onion juice contains 1−22 μmol of lachrymator. If sulfuric acid had formed in a 1:1 ratio, the resulting pH would have been enough to turn the litmus red. Testing vinegar on the litmus confirmed the setup could detect acidity.

Finally, it's important to note that the lachrymator isn't a single compound. NMR analysis reveals it as a 19:1 mixture of (Z)- and (E)-propanethial S-oxide. These aren't groundbreaking findings, but they highlight how easily inaccuracies in familiar topics can slip by—and make us wonder what happens with subjects we know less about.