Urgent care centers (UCC) are increasingly common and maligned by some as “docs in a box.” They provide a range of acute care services that could be found in a primary care office but have better hours and shorter wait times – they are more convenient. A study reported in Health Affairs looks at how they have impacted Emergency Department (ED) use and cost by looking at insurance claims.

Urgent care centers (UCC)

Commercial carriers have hoped that the lower price UCC services would be an acceptable substitute for the same, more expensive, service provided by the ED. There is no doubt that on a one-to-one replacement, the math is in their favor. As a result, UCCs have expanded rapidly, representing “the highest-volume alternative care site” to EDs as well as telemedicine and “retail clinics,” those pharmacy-based care centers. UCCs have many essential services and can maintain low prices because they have no sizeable, fixed overhead for expensive laboratory and imaging equipment – think CT scanners and multiplex blood analyzers. There is little doubt that UCCs replace ED care, but do they save money?

The fly in the ointment, as we shall see, is that the lower cost of a UCC also lowers the hurdle from staying at home and not seeking care at all.

The Study

Researchers analyzed the claims of a national managed care insurer for 2008 through 2019. Medicare beneficiaries were excluded. The claims covered policies with high deductibles or were restrained by being HMOs or preferred provider organizations – we are talking about insurance for many adults, but not our seniors. They further focused on “low-acuity” conditions, like a sore throat or sports injury, where ED care's potential overpowered need. All of the claims data were grouped at the zip code level and population data from the 2010 census.

A few quick caveats. There was no information on which insurance plans each patient had; a high-deductible program might move more people towards UCCs over EDs – a patient’s freely made choice was unknown. The acuity of care was based on the discharge diagnosis, not the patient's reason upon arrival. The patient’s perception of their need drives their selection, so establishing acuity of the need on a final diagnosis shifts the decision to the physician, a less involved party. Finally, the study did not consider how UCC visits impacted primary care visits, a significant limitation given that UCCs are found in the same place you find physicians, rarely in “underserved” areas. [1]

The population was slightly more female, 56% and relatively young, mean 29.9 years old. There were nearly 13 million claims for lower acuity care in both the EDs and UCCs for a rate of use of 57 visits/1,000 beneficiaries annually.

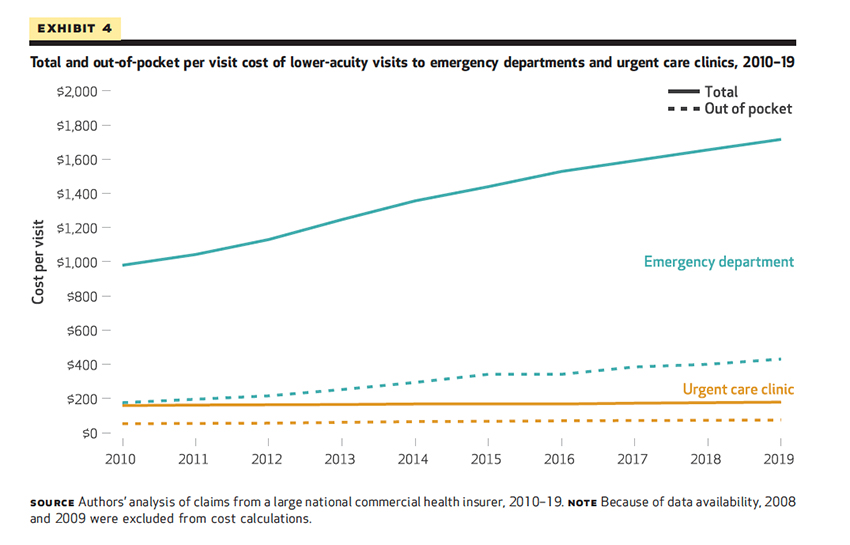

- During the study period, ED costs rose at a much higher rate than UCC expenses.

- During the study period, ED visits declined in general. In zip-codes without a UCC, ED use declined by 31%, while in zip codes with high utilization of UCCs, ED use declined by 39%. That 8% difference could accrue to increased UCC visits.

- Remember the fly in the ointment? Every decreased ED visit was associated with 37 more UCC visits. That changes the math of cost completely. To show net savings, 37 UCC visits must be less than 1 ED visit. Using the researchers' figures, the EDs’ low-acuity visit cost of $1,716 was replaced by 37 UCC visits at $178 for a total of $6,758.

As the graph shows, out-of-pocket costs rise – we pay for the convenience of UCCs because even though the cost per visit in a one-to-one substitution favors UCC use 10-fold, it also results in lowering the bar to use the service at all and the total costs rise by 4-fold. And whether these lower-acuity services improved health outcomes remains unknown – that would be a far more difficult value to identify.

The take-home lesson for today is that simply providing a lower-cost site of care does not mean lower costs. Lower costs are realized only when substitution is one-for-one. As lower costs substitutes are used more frequently, our aggregate expenses may well be higher. Fixing the pricing in healthcare is, as I often say, complicated.

[1] Private equity has made a considerable investment in UCCs, and they always focus on the bottom line. As the study shows, those zip codes without a UCC had 3.2% more seniors (fixed payments), 3.6% more residents living below the median poverty level (lower payment, e.g., Medicaid), and 3.9% more disabilities (higher care acuity). UCCs in underserved areas are not necessarily money-makers.

Source: The Missing Evidence: Urgent Care Centers Deter Some Emergency Department Visits But, On Net, Increase Spending Health Affairs DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01869