Access to adequate water contributes in various ways to Americans’ quality of life – for bathing and drinking, of course, but also for various manufacturing processes, disposal of human waste, and irrigating much of the farmland that provides our food. But the water woes of the Western U.S. are severe and worsening, threatening our prosperity and quality of life. As a fourth year of drought looms, California water managers predict that state-run reservoirs, including massive Lake Oroville, will not be able to provide much water for cities and farms next year.

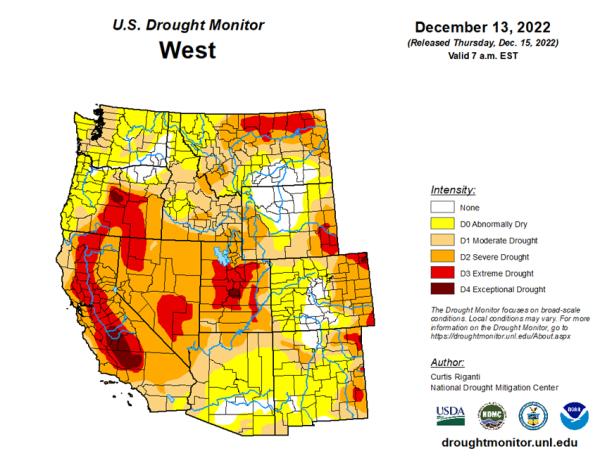

Currently, as shown on the map below, 99.5% of the state is in moderate, severe, extreme, or exceptional drought. Over half of the state, including the farm-rich Central Valley, is experiencing extreme or exceptional drought.

Credit: David Simeral, Western Regional Climate Center

The situation in California — with its outsized population, massive agriculture, and recurrent droughts over much of the past decade — is particularly tenuous because of a severe deficit of groundwater. For years, farmers in the Central Valley have liberally extracted water from the region’s aquifers to compensate for reduced supplies from reservoirs, canals and aqueducts. As water levels have dropped, farmers, homeowners, and municipalities have dug deeper and deeper wells, but such measures only delay the inevitable: The incidence of well failures is increasing.

California is not alone. The map shows that other Western states also are facing significant drought conditions. As described by the EPA, stress on water supplies and the nation’s aging water treatment systems can lead to a variety of consequences for communities, including astronomical water prices, increased watering restrictions to manage shortages, seasonal loss of aquatic recreational areas, and expensive water treatment projects when local demand overcomes available capacity.

A problem of distribution, not supply

Domestic water use is necessarily high in the dry Western U.S. states because of low humidity and evaporative losses. This problem is amplified by sunny conditions, high temperatures typical of the Southwest, and dramatic population growth in cities such as Phoenix.

With wise public policy, all these needs for water could be accommodated because America does not have a water supply problem; it has a water distribution problem. There is plenty of water, but not where it’s needed.

We suggest a remedy for the maldistribution that dovetails nicely with congressional and White House initiatives to improve and expand the nation’s infrastructure

Few have focused on ways to increase supply, despite the ample water in other parts of the country. Therefore, to address the water shortages in Western states, we propose a major new infrastructure project that would revolutionize water distribution in the United States and greatly advance development of the western half of the nation: long-distance pipelines and aqueducts.

In much of the West, rain is sparse. Except for parts of the Pacific Northwest, water comes largely from a variety of sources other than precipitation. California, for example, has a hodge-podge of sources, one of the most important of which is the Colorado River, which supplies most of the water for farm irrigation and urban areas in the southern part of the state. Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and Mexico all share the river, which is itself increasingly threatened by drought. Flows have dropped some 20 percent over the last two decades.

But there is ample, and even an excess, of water elsewhere. The largest river in the East, the Mississippi, has about 30 times the average annual flow of the Colorado, and the Columbia has close to 10 times. Water from these and other large rivers pour unused into the sea, and the Great Lakes are another huge possible water source.

Thus, the West’s chronic water shortages result from a failure to appropriately redistribute our nation’s abundant total water resources. We currently transport oil, but not water, across America, although large volumes of water can move through pipelines, tunnels, and aqueducts with perfect safety over long distances.

An interstate Water System

We envision a major combined federal and private hallmark program for the nation — an Interstate Water System (IWS), which would rival in importance and transformative potential the Interstate Highway System, whose formation was championed by President Dwight Eisenhower. We already store water in man-made reservoirs – that is, lakes – and move it to where it is consumed, and the IWS would be designed to expand America’s water-related infrastructure by transporting water from places of abundance to where it is needed.

The IWS is feasible. Assume that an initial goal might be doubling the water flow, averaging about 20,000 cubic feet per second, to Colorado River system reservoirs. Pumping Mississippi River water to an altitude of 4,000 to 5,000 feet likely would be needed to supply California reservoirs Lake Mead (altitude 1,100 feet) and/or Lake Powell (altitude 3,600 feet). We estimate that it would require fewer than ten power plants of typical one-gigawatt size to provide the energy to move water halfway across the nation to double the flow of the Colorado River. (Gravity-driven flow turning turbines below its reservoir lakes would eventually regenerate much of the input energy required.) North-south pipelines from the northwestern tip of California, where rain is plentiful, to the central and southern parts of the state would be easier and less expensive.

The impact of an IWS would be enormous. It would create innumerable jobs, provide many construction and other business opportunities, and facilitate national growth and development, including greatly enhanced development of many lightly populated dry areas in the West and Southwest.

The IWS would be expensive but it would pay for itself many times over due to the resultant economic expansion in the West. It would take shape over years, as did the Interstate Highway System. And like the national highway system, its impact would be enormous. We should start building it now.

Joseph D. Schulman, M.D., a scientist, former professor, and Chairman of Genetics & IVF Institute, lives in the American East and West. John P. Schaefer, Ph.D. is a chemist, former President of the University of Arizona, and a director of Research Corporation Technologies. Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is the Glenn Swogger Distinguished Fellow at the American Council on Science and Health.